Catholics cannot "stay out of politics"

Why Catholics have a responsibility to engage in the political

“I try to stay out of politics.”

We’ve all heard this from fellow Catholics. Most of us have said it ourselves.

But Catholics have a unique gift to give the political world.

When Catholics have political discussions, it is not only good for our country, but it also fulfills Christ’s command to love our neighbor.

Politics is a Conversation

Like most Americans, I was told there were two things you can never bring up in polite conversation: religion and politics.

G.K. Chesterton disagrees.

“I only ever talk religion and politics. There is nothing else to discuss.” G.K. Chesterton

As usual, Chesterton is dead-on. Religion and politics deal with the two most important aspects of human life. Religion deals with how we ought to relate to God and politics with how we ought to relate to each other.

These correspond to the greatest commandment: Love God and love your neighbor as yourself.

I understand the desire to stay out of politics. Who can keep up with every bill in Congress or every drone strike in the Middle East? But politics is more than just the current event of the day. It is an ongoing conversation about the highest good.

Politics is the ongoing conversation between friends about how to achieve the common good.

Conversation — Two or more people expressing how they see the world.

Friend — a person whom you love (will the good for)

Common good — that which leads to the flourishing of the society and the individual

(Note: The “Common Good” is a Catholic concept distinct from the totalitarian idea of the “greater good” where the good of the individual is sacrificed for the collective.)

For this political conversation to work, it must be rooted in reality. And Catholics are uniquely positioned to root it.

Politics of the Real vs. Politics of the Ideal

D.C. Schindler wrote a book about a concept called “The Politics of the Real.” In the Politics of the Real, the political conversation is about a shared reality—the world and the God that exists beyond us. I contrast this with what I call the Politics of the Ideal, a tendency in modern politics that tends towards ideology.

The Politics of the Real asks:

How did God create us to live?

How can we build our society to live that way?

The Politics of the Ideal asks:

How do I think we should live?

How can I build our society to live that way?

The Politics of the Real recognizes that God made us to live in society with one another and therefore must have principles for us to build a society. The Politics of the Ideal either ignores or actively rejects God’s ordering of the universe. It moves the conversation away from reality and toward ideology.

The Politics of the Ideal has dominated our political discourse for the last few centuries. All modern ideologies are Politics of the Ideal. They begin by imagining the ideal society:

Marx dreamed of a classless society

Hitler spoke of a mythical Arian race

Rousseau imagined a stateless, godless society

Hobbes imagined a war of all against all

Practically, these are all mythologies—imaginary, perfect worlds. They are like new Edens, but instead of God creating man, these stories are of man creating himself.

Our political discourse is trapped in the Politics of the Ideal, albeit on a smaller scale than “master race” or “classless society.” The right tends to imagine a perfect world in the past, the left a perfect world in the future.

Since politics is trapped in this argument about the ideal, Catholics want nothing to do with it. We prefer to live in safety outside of the ideological squabbles. But we are the best positioned to refocus the discussion to the Politics of the Real.

The Politics of the Real is a conversation about the reality we all share. Anyone can participate because everyone lives in reality (duh). The Politics of the Ideal is about a shared ideology, which means only people who share the “ideal world” vision can participate. So in the Politics of the Ideal, conversation breaks down.

Babel and the Breakdown of Conversation

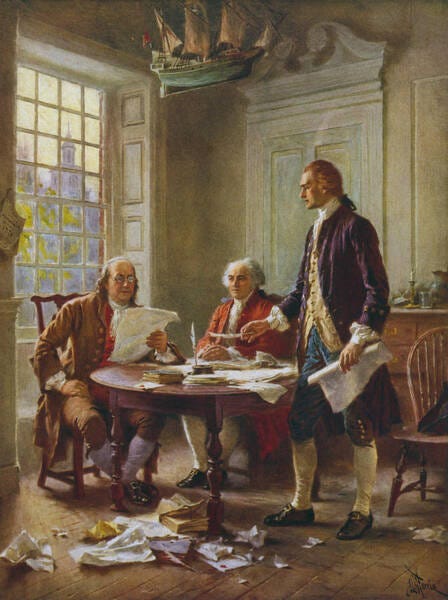

The Tower of Babel, described in the book of Genesis, illustrates what I mean.

The story begins with a conversation about the ideal: Let’s build a tower that reaches heaven. That conversation is not based in reality (a tower cannot reach heaven), and the project quickly degrades. Since none of the people are rooted in reality, they have competing concepts of what heaven is. Since they exist in different realities, they cannot understand each other. So, God confuses their language.

In any conversation, disagreements will arise. To be productive, those disagreements need common ground. In The Politics of the Real, the common ground is reality itself. In the Politics of the Ideal, the common ground is the myth. The conversation will only continue if both parties believe strongly in the myth. If one person starts to believe in the myth less, they are expelled from the conversation

And that is exactly what is happening on the American left right now. If you look at the chart below mapping intellectual disagreement, you can see there’s more variety of opinion on the right than there is on the left. This is not isolated to the left or the Democratic Party. This will happen to any political network that is rooted in ideology over reality. And for the last few decades, the left has been firmly rooted in ideology.

The left tried to create an impossible world. A world where men can marry men, men can become women, and mothers can kill their babies. That impossible world could not hold. So it is falling apart.

It was always going to break apart. As the tower got higher and higher, it became narrower and narrower. And only the true believers could stay on. That’s just what happens.

Disagreement Among Friends

The Politics of the Real allows for disagreement. When political discussions are confined to ideology, everyone who disagrees is an enemy. So fewer and fewer conversations can be had. On the other hand, when the political conversation is about reality, disagreement is not only allowed. It is encouraged.

There is humility in the Politics of the Real. There is a recognition that your and my perspective of reality might be incomplete. So in true political discussions, there is room for disagreement. We are discovering reality—discovering God—together.

The Catholic Church has given us a head start in the conversation. For the last few centuries (while other thinkers were inventing ideologies), popes and theologians were busy discussing reality. That discussion resulted in a body of teaching we call “Catholic Social Teaching (CST).”

CST is not an instruction manual for building a Catholic state. Nor is it a “third way” between conservative and liberal, as many describe it. It’s the field of play for every regime and political party to follow. When an issue arises in modern politics, we can examine it in light of the principles of Catholic Social Teaching. Those principles include:

Universal human dignity

Universal destination of goods

Solidarity

Subsidiarity

Preference for the poor, etc.

Some issues are easy. For example, legal abortion clearly violates the principle of human dignity. But most issues are not obvious:

How many immigrants from which countries should America let in per year?

Should America launch an attack to end Iran’s nuclear program?

How should healthcare be administered in our country?

CST allows virtuous and intelligent minds to differ on these questions. Ideology, for the most part, does not. A communist and a fascist would answer these questions in predictable ways. Devout Catholics will differ, and that is a good thing. We need to check our understanding of Catholic Social Teaching—of reality—against the perception of others. That’s how we grow as individuals and a community.

If you’re an ideologue, disagreement makes someone an enemy. If you’re a Catholic and you live in the Politics of the Real, disagreement makes someone a friend.

Catholics Must Engage the Public Square

This is why Catholics must engage in politics. Our Church has given us an invaluable tool for political discussion. We have a set of principles we can use to describe God’s plan for human society.

The only thing stopping us is that we don’t want to disagree. We don’t want to vote for or even talk to politicians who disagree with Catholic teaching (or our interpretation of Catholic teaching). We assume because we disagree that we are enemies. That is a grave error. A Christian does not assume enmity. A Christian assumes friendship. And even when we are proven wrong and the person is our enemy, we love them anyway.

A Catholic society will not be built if Catholics sit and wait for it to be given. A Catholic society is built by individual Catholics being the salt of the earth, being the leaven in the loaf that makes it rise. We must go into every crevice of society to preach the gospel. And that includes the political arena.

God turns chaos into order, disagreement into understanding, and enemies into friends. When we remove ourselves from political conversation, we refuse the good God wants to bring out of that conversation.

To refuse to engage in politics is to refuse the second half of the greatest commandment: to love your neighbor. We must love our neighbor enough to disagree with him. When we do that, we begin to build a Catholic polity.

Hey! Glad to see you here on Substack. I have followed you on Insta for a few years. Keep up the good work!

I would argue that every modern political ideology is idolatry of some form. These political ideologies elevate a particular or even minor good—nation, race, equality, autonomy—to the supreme good. We can think of communism as idolatry of economic equality, fascism as idolatry of the state, Nazism as idolatry of race, and liberalism as idolatry of the self. The common good as taught by the Catholic magisterium is rightly ordered to God above all and then to neighbor.

Furthermore, the nature or essence of government is to resolve controvertible issues according to some conception of what is true and good. It is the magisterium that teaches the full deposit of faith and morals and thus what is good and true. In other words it is impossible to separate politics from the common good and likewise impossible to separate the common good from the Catholic Church.